I was talking to a friend the other day about personal finance while at Starbucks. The dilemma was whether or not she should continue to take the Bay Area public transportation to work, or start driving. Ironically, driving would be cheaper, but not by much, the cost difference was roughly $15 a week. To throw the dilemma of perpetuity out of the question, she is also planning on moving and switching jobs in 4 months.

A rough calculation taking in consideration only the difference between gas cost and public transportation fees shows that at a difference of $15 a week for 4 month would save at most $300.

15 dollars/week x 4.5 weeks/month x 4 months = $270

The result also includes a $30 margin of safety accommodating for some combinations of an increase in transport fees and/or a decrease in gas prices that result in a net increase in total savings. We will ignore situations that result in less net savings (some combination of decreasing fees and/or increasing gas price.)

When I brought up the relative insignificance of $300 over the 4 month, and that given the stress of driving in traffic, I probably would choose to continue taking public transport. The response was the sound bite of the personal finance gurus of the world: “but every bit counts.”

Eh, no it doesn’t.

The rifles of personal finance gurus seem to always be aimed at these insignificantly small cash expenditures. They’ve termed these expenditures microspending, and the $3 latte at Starbucks is the favorite punching bag for many. Other targets include frequent haircuts, bottled water, and more recently, an Australian real estate mogul denounced avocado toasts to be the cause for Australian millennial’s inability to afford home ownership. Right, because the $15 spent on avocado toasts is the reason why young people cannot afford million dollar Australian properties. It is definitely not the fact that Australia has seen a massive influx of foreign investors sautéing the real estate market, pricing the properties completely out of reach, and forcing Australians to keep up with a higher household debt-to-GDP ratio than even Canada1 (with its own housing bubble primed to explode). According to Rider Levett Bucknall’s Crane Index, Sydney alone has more cranes (350) for residential building than all of North America combined (<200)2, Is that not a sign of a overextension? Yet Australian millenials shying away from these spectacularly stupid speculative properties is not viewed as a sign that the real estate market might be overextended and overpriced. The grown-ups have chosen to blame the Australian millenials for spending their money on lattes and avocados instead of sheepishly sing to the slaughterhouse and holding the bags of these overpriced properties. It’s one thing to criticize the lack of saving, it’s completely different when a real estate mogul criticize a generation for not buying (his) real estate.

Property bubbles aside, the issue with microspending is multi-leveled. At the first level, the calculations often done to show how much these microexpenditures compound is naïve at best, down right misleading at worst. At the second level, the vilification of microspending ignores some important principles of human psychology. Both of which leads to the third level of error, the ignorance of nonlinearities of life.

Bad Math

In Alice Schroeder’s biography of Warren Buffett Snowball, there was an interesting passage of Buffett estimating his savings to be $300,000 if he just lengthened the time in between his haircut appointments. Yet Warren Buffett did not become rich by penny pinching on haircuts, he got very rich by being one of the greatest value investors of all time. A naïve interpretation of this would be “if Buffett pinched haircuts and he’s rich, I can get rich by pinching haircuts.” This is a bad take and ignores that the haircut pinching advice being public is conditional on Buffett’s success, not the other way around. In other words, without such sharp eyes for mispriced intrinsic values, Warren Buffett would not have found his wild success, and the whole haircut thing would be lost in irrelevancy. It wasn’t the haircut that made Buffett, it was Buffett that made the haircut.

Yet it is naïve takes like this that gets the attention. A $3.50 daily latte, compounded over 30 years at 6% is worth $106k, according to a Business Insider article3. Yet this simplistic calculation is not adjusted for inflation, does not take into account tail events of various kinds, and assumes too stable a compounded interest.

First, if we take inflation into consideration, assuming we take the Fed’s 2% target at face value, then the nominal 106k in 30 years only has real purchasing power today of $58k. In other words, if you are putting in a non-inflation adjusted $1260 every year for 30 years ($37,800 total,) your compounding account will actually give you only about $58,000 of purchasing power at the end of 30 years. This is adjusting for inflation at the output. Another way to think about inflation would be that the cost of the latte would rise 2% a year due to inflation, so in order to save the increasing cost of a latte, the amount that’s necessary to be put into the bank would increase 2% a year. This is adjusting for inflation at the input, and by the 30th year, each latte would cost $6.33 each instead of $3.50, and your yearly contribution would have increased from $1260 to $2238. In this case, then your inflation adjusted output of $106,000 at the end of 30 years would require an input of $51,116 over 30 years. So as you can see, it’s not as astronomical a return as it originally seemed, because the pernicious effect of inflation is a compounding effect as well.

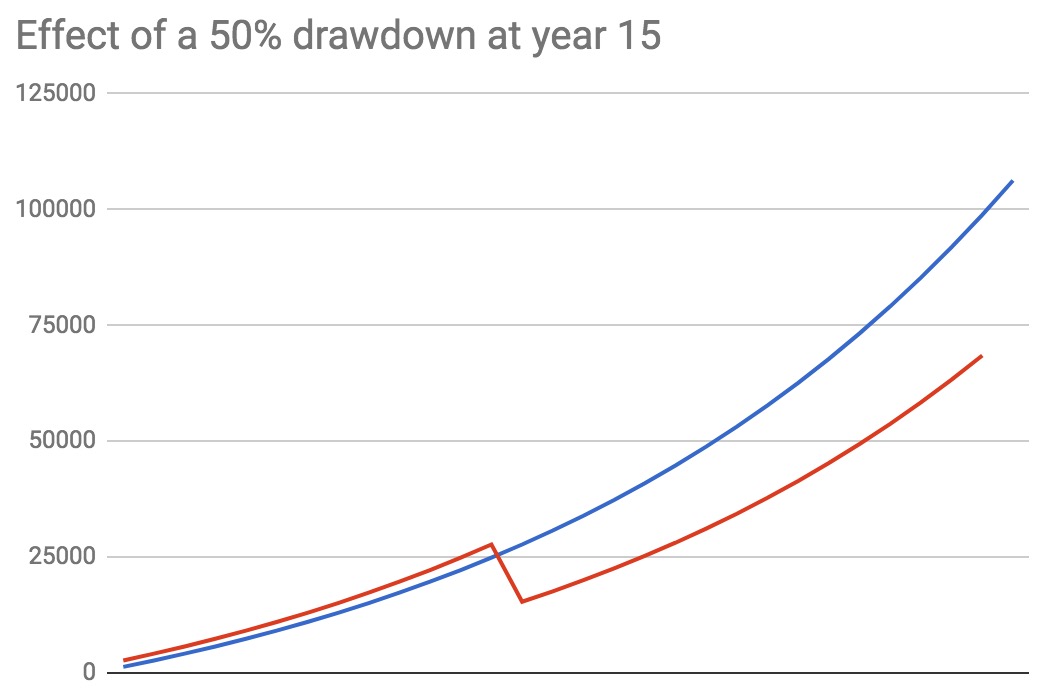

Second, we would look to add tail risk into the model, where we induce a 50% drawdown in the middle of the 30 years due to a stock crash, which is not an unreasonable assumption (remember 2000 and 2008). In this case, in the 15th year of the 6% annualized return, the compounding interest would have reached $30,700, and the market crashing 50% brings your portfolio value to $15,350, and you start compounding again at 6%. After 15 more years, your total balance is only $63,265, again not counting for inflation. One word of caution is this, if the drawdown occurs early, it does not matter as much. If a drawdown occurs late, it does massive damage to your portfolio. Extreme examples are 50% drawdowns occurring in the first year, in where you see your losses at $600, compared to the 30th year, where the damage totals over $53,000. There is no way to tell which years this will happen, and shows the importance of hedging tail risks, especially as you approach the end of your investment horizon.

Bad Psychology

Danny Kahneman’s book Thinking, Fast and Slow is one of the most important book published in the last 20 years, and is a book I recommend to everybody. However, what I found to be one of the most pernicious systemic biases was almost glossed over in the book, and is worth taking a look at here. Ego depletion, Kahneman writes, is the finding by psychologist Roy Baumeister that “all variants of voluntary effort (cognitive, emotional, or physical) draw at least partly on a shared pool of mental energy… and has repeatedly found that an effort of will or self-control is tiring; if you had to force yourself to do something, you are less willing or less able to exert self-control when the next challenge comes.”

This is an incredibly important insight with far-reaching consequences. For one, it is a subtle refutation of the common idea that the initial inertia of making a change is the most difficult. The experiment provides counterevidence that it actually gets more difficult as time goes on. One way to view the results is the static view that longer you hold off that piece of cheesecake, the more difficult it will be for you to hold off that piece of cheesecake. A slightly more dynamic view however, is that the longer you hold off that cheesecake makes you more likely to eat a tub of Haagen Dazs later, or to eat an extra slice of pizza later. But the most important implication of this study is that all of these mental effort draws upon the same proverbial mental gas tank of discipline, and that the more effort exerted to deprive yourself of an occasional slice of cheesecake might lead you to go on Amazon and order a new TV, or to engage in other risky activities that has nothing to do with the original activity precluded yourself from partaking. The subtlety here that Baumeister discovered is that life is not a simple system of isolated events in a vacuum having nothing to do with each other, life is a complex system with many interacting forces that are all entangled with each other in an intricate web. In other words, the act of exerting self-control to refuse spending $3 on a cup of coffee does not end with you walking away from Starbucks declaring victory over your impulse, but it will continues to have an effect on you in the future. So two seemingly completely unrelated activities such as refusing a cup of coffee a couple of days ago and splurging on a new jacket today might indeed be deeply connected. This is something rarely explored in academia, because to explore what the higher order effect of an action is, one has to be aware of where to look. Yet if one knew where to look, one would tautologically already know about those higher order effects. It’s a complete Catch-22. But in this case, Baumeister have become one of the rare academic psychologists to discover the process of something that is inherently dynamic and thus applicable to real-life. So one has to at least keep in mind the possibility that an innocuous act of declining the impulse to spend $3 on coffee might lead to more expensive splurges later on.

Bad mindset

So far we’ve looked at bad math and bad psychology of a popular personal finance dictum of every bit of saving matters. The arguments above is not meant to discourage saving. Saving money is a good habit because the saved capital is what provides the cushion to be able to take risks that drives life forward. However, it must be realized at this point that is it does not matter howoften you manage to be frugal, but it only matter how much you save in total. In other words, it matters not the frequency or duration of self-discipline, it matters what you exhibit discipline in and what the payoff for that discipline is. It is the payoff function that matters in life. So here lies a wonderful example of nonlinearity in life, because if Baumeister is correct, then it is completely reasonable to think that it may take much more mental effort to save $1000 by skipping 300 trips to Starbucks than it does to simply avoid buying a new TV once next Christmas. In fact, by forcing yourself to skip Starbucks so many times, you might be unnecessarily incurring a very significant risk/cost upon yourself by depleting a very finite supply of discipline and increase your chance to make a very large foolish financial decision somewhere down the line that wipes out all savings accomplished. Penny-wise and pound-foolish is a sure ticket to the poor house.

Bibilo

2.http://assets.rlb.com/production/2017/02/01000131/2017-01-Crane-Index.pdf

Click to access RLB-Crane-Index-Australia-Q4-2017.pdf

3.http://www.businessinsider.com/how-to-make-iced-coffee-french-press-daily-cup-costs-100000-2017-7