I read Stephanie Kelton’s The Deficit Myth recently. Like it or not, Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is going mainstream. Much like bankruptcies, most economic regime shifts occur very slowly and then all at once, and Kelton’s book will likely be one of the most important for-public-consumption academic books driving economic policy decisions for the next decade plus. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, one of the most polarizing politician of our current time has already referred to the theory to be “absolutely” necessary as “a larger part of our conversation.” 1 The Theory has been repeatedly referenced to by economists, politicians and even Bill Gates.2

One central thesis of The Deficit Myth is that MMT can be used prescriptively rather than simply descriptively. As someone whose day job is pretending to be a real doctor, the difference between the two ideas is pretty clear. Take Koch’s Germ Theory as an example, the theory itself is a description of how diseases happen. The theory proposes that it is the existence of and invasion of pathogens that cause diseases. It supplanted the equally descriptive Miasma Theory, which theorized that diseases came from the intake of rotten smell in the air from rotting matters. Another example closer to my field of work is that dental decays are caused by acid produced by the bacteria S. Mutans. These are descriptions of how things are, and does not offer any prescriptive measures going forward. The prescriptive side of Germ Theory is then: assuming that pathogens are the cause of disease, therefore by eliminating the pathogens, the disease will then disappear. This elimination of pathogen does not necessarily have to be specifically targeted only to the pathogen; a scorch-earth type of elimination is equally efficient. This is clear in dentistry that physical destruction (drilling) and reconstruction (filling) of the tooth eliminates the pathogen and thus the disease, or that injecting bleach will eliminate covid. (Big if true, Donnie.) The Deficit Myth proposes that MMT is not only a descriptive framework of how our monetary system works, but that we can use MMT to make prescriptive policy changes to better the world.

So what does Modern Monetary Theory actually describe? In short, it is a model of our post-Gold Standard and post-Bretton Woods, fiat-based monetary system. The first fundamental idea of Modern Monetary Theory is that there are two different kinds of limits: real and arbitrary, and that we (the US) should learn to “distinguish artificial barriers from legitimate constraints.” 3 What Kelton means is that there are real and artificial limits to what material living standards an economy can support. A crude analogy of mine is that if the reason we cannot make a car go faster than 300 MPH is physics or engineering, then that is a legitimate constraint. But if the reason for that inability is because the legal speed limit is 80mph, then that is an obviously artificial barrier. The difference is obvious. We can easily change the speed limit with a few strokes of a pen, but we cannot break the laws of physics. Same thing with economics, MMT says.

After we accept that there exists a difference between real constraints and artificial barriers, MMT further postulates that in a fiat currency regime, (such as the US, who produces US dollars without any commodity backing) all constraints on noninflationary government spending are artificial. The key word is noninflationary. For MMT the real constraint of a macro-economy is inflation. What this means is that government can (descriptive) and should (prescriptive) print and spend money into economy so it can produce as much goods and services as it realistically can without triggering inflation.

This is the fundamental tenet of descriptive MMT: that inflation is the real limit to the productive capacity of an economy and therefore it is also the limit to the material living standards of a fiat country’s citizens, and all other constraints are artificial. The corollary to this description is that if there is no inflation threat, then government sector can spend by injecting new money into the private sector up to the point where inflation occurs without any adverse consequences. This may sound circular, that if we assume inflation is the only adverse consequence, then there will be no adverse consequence if we assume inflation does not occur. As we will see later, circularities can run the other way very quickly in real life.

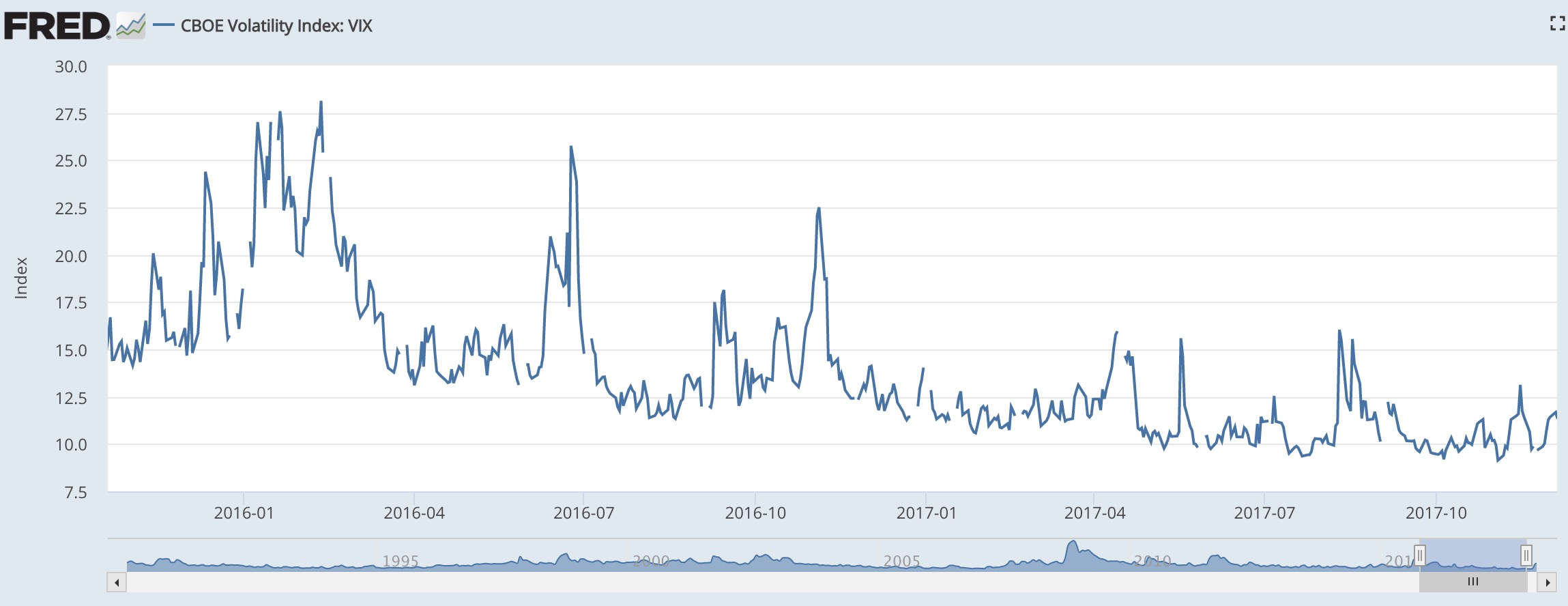

So, if we assume away inflationary risks, then any deficit that resides on the federal government’s balance sheet does not matter. Under the MMT framework, fiscal austerity for the sake of budget balance in a fiat regime is silly, and any criticism of noninflationary deficit spending is misguided. Empirically for the last 20 years, inflation has not been a major problem in the US, yet the US has printed trillions of dollars running the dreaded twin budget and trade deficits. None of the stern warnings of the deficit hawks from Ross Perot to Ron Paul came true. Even Wall Street traders were not impervious to deficit hawking. Paul Tudor Jones and Michael Steinhardt have been worrying about the federal debt since the mid 80s, as their interviews with Jack Schwager in the Market Wizards have dated. 4 Yet since America had not experienced major inflations in the last 20 years, there has not been any negative consequence of the huge expansion in government debt from running continuous deficits. Empirically, descriptive MMT has been pretty spot-on in its explanation of the post-Bretton Woods fiat regime. The trouble with MMT is its use as a prescription going forward.

If we revisit the difference between descriptive and prescriptive, we can see that the prescriptive tend to be the logical consequent of the descriptive, if and only if we assume no major changes (stationarity) to the described process going forward. Such stationarity assumption has worked remarkably well in medicine because the process of disease pathogenesis never biologically changed since the discovery of Germ Theory. Yes, bugs mutate and develop resistance after repeated exposure to the same therapeutic agent, but the pathophysiology of a Staph Aureus infection has remained the same. Only because the pathogenesis is the same, we can use the descriptive knowledge to prescribe medical interventions for future staph infections. Had the world been so cruel such that once the pathophysiology of a disease is known, the pathogen alters its mode of infection, medicine would be much less successful than it currently is.4

Human are not bacteria. When it comes to human affairs, an assumption of stationarity is not valid. George Soros has been writing about reflexivity and fallibility since Alchemy of Finance in the 80s. In his 2014 paper Fallibility, Reflexivity, and the Human Uncertainty Principle, Soros explicates the definitions. Fallibility, Soros writes, occurs when “the participants’ views of the world never perfectly correspond to the actual state of affairs.”5 In other words, one’s description of how the world works often isn’t how it actually works. Soros then defines reflexivity to “apply exclusively to situations that have thinking participants” with abilities to both understand (describe) and manipulate (prescribe) the situation that they are involved in. Economics is obvious one of those situations. An attempt to prescribe often alters what was described. Under fallible conditions, the relationship between cause and effect is always imperfectly understood. Upon reflexivity, cause and effect becomes circular and feed upon each other, which deprives the observer of a true independent variable. According to Soros, fallibility and reflexivity is inherent in the human condition, and we have to wrestle both with whether or not our explanations for the past is correct and if such explanations can be depended on going forward.

Fallibility of MMT

One of the fallibility concerns with MMT is that even if we assume the Theory is descriptively correct, there are still some parts of the Theory that has not been ironed out. MMT says that government does not have to tax first in order to spend, that is technically true. But reality is, neither do you or I. We all have credit cards that allows us to spend before actually paying. This is the definition of credit. Government can “print money” to pay for Boeing fighter jets much like how we can drive a brand new SUV off the lot with little more than a minimal down payment. But make no mistake, both examples of spending is funded by credit, and what determines creditworthiness is real productive capacity. For an individual, creditworthiness depends the ability to take ownership of the product of one’s productive capacity. This is a highbrow way of saying you only get credit if you have something valuable, or have an ability to generate value. Therefore, if an individual does not have and cannot produce anything of value, or cannot claim ownership of the generated value (for example, under a 100% tax environment,) credit cannot exist for the individual. The creditworthiness of a government on the other hand resides in its ability to tax its citizens’ real productivity, which is determined by the nation’s nature resources, labor pool, capital supply, and technology. This is why developed market (DM) countries with more productive labor, deeper capital base, and better technology can borrow at far better terms than Emerging Markets (EM) countries, because the tax base is much larger in DM countries.

Kelton further argues that the massive size and deep liquidity of the US Treasury Bond market demonstrates that there are excess demand for US T-Bonds, and therefore the US government can soak up the excess bid and sell more T-Bonds and be able to deficit spend much more than we currently are. But I would suggest the excess demand for T-Bond is not an intrinsic property of US T-bonds, but it is rather the excellent creditworthiness of the US that allows the demand for US T-Bond to outstrip supply. The world demands US T-Bonds because the US is viewed to be creditworthy, and the US is creditworthy because of Uncle Sam’s perceived ability to tax the real productivity of the world’s biggest economy. This is what everyone means when they say US T-Bonds are the “safety trade.” Therefore while it is correct the government doesn’t need to actually tax in order to spend, it is not true that government does not rely on taxpayers as Kelton claims, or that “taxpayers do not fund anything” as MMT economist Bill Mitchell has written. The taxpayers’ productivity is the ultimate source of their government’s perceived creditworthiness, and this real productivity by the taxpayers is the source of the government’s spending. 6

A second point to the fallibility of MMT involves Kelton’s prescriptions for many of today’s societal ills. We have already seen that when the lens switches from descriptive to prescriptive, we not only have to be certain that our models does well explaining the complexities of past, but have confidence our model will perform in the future. This is no easy task. As Soros says, when “confronted by a reality of extreme complexity, we resort to various methods of simplification.” MMT is no exception for this simplification. MMT compresses the complexities and textures of societal ills to a singular cause: a lack of (public) investment. There is a common meme that MMT is a political stance masquerading as an economic theory. When it comes to the prescriptive side, the meme is a not completely untrue. For example, Kelton states that US has what she calls a “good jobs deficit” in that “the flow (of money) grant good pay and great benefits to a small portion of fortunate Americans and meager pay and little-to-no benefits to a great many more.” In other words, Kelton has found the increasing wealth and income inequality to be unpalatable. She argues that MMT teaches “any currency-issuing government has the power to eliminate domestic unemployment by simply offering to hire the unemployed,” and adds that MMT recommends “these jobs pay a living wage and that the work itself should serve a useful public purpose.” She contends that this nondiscretionary government spending would act as an automatic stabilizer for the business cycle. During economic downturns, the number of “good-paying” federal jobs would automatically increase due to private sector job cuts and therefore increase government spending to offset the reduced private spending from the downturn. “Universal job guarantee is the MMT solution to our chronic jobs deficit.” Kelton exclaims.

This solution is of course extremely unpolished. First we already discussed that the ability to tax the real productivity of a country is the fundamental source of government spending. Taken to an extreme, if a country cannot produce anything of value, then it matter little if everyone is in a well paid position —all goods/services would have to be imported and the domestic currency of the country would not be accepted for anything of value. Second, if the federal government become the undisputed “employer of last resort” offering guaranteed “good” wage, then what is the mechanism to deter poor job performance? To put crudely, if one cannot be fired, what incentive will there be to at least perform the duties to a minimum standard? What would this guarantee do to the cost of employment in the private sector? What about the business that cannot accommodate such federal wages? Should such businesses be subsidized? What about the potential retirees who want to return to the workforce to collect a paycheck? What about ex-criminals? What changes need to be made for workplace safety to accommodate this new group inside the labor force? How will this affect employment law? Very quickly we can see how the complexity of this one single policy can spill over into every facet of employment. Universal job guarantee seems destined to reenact the old Soviet saying of “we pretend to work and they pretend to pay us.”

Kelton subsequently argues that it is actually not sufficient to have an amped up nondiscretionary stabilizer, but we should increase our discretionary spending as well. She presents that the country has a healthcare deficit where the costs are high and the outcomes are poor. Her solution is for the federal government to spend into improving healthcare infrastructures by building more clinics, educating more doctors, and that in turn will increase the capacity of the economy, which should relieve any inflationary concerns that this spending will create. Kelton has the same prescription for many other what she calls “real deficits” of the country such as “education deficit”—more spending into K-12 and universities; “infrastructure deficit,”—more spending to build roads and bridges; and pretty quickly we end up in the leftist deep waters of “climate deficit” – more spending to fund the Green New Deal; and “democracy deficit.” – more spending into ??? Of course, just like the trouble with Universal Job Guarantee, the complexity of each solution and our fallibility to understand them presents significant concerns, and this presents significant risk for the well-intended prescriptions of MMT.

The final point of MMT’s fallibility has to do with inflation. As previously stated, MMT’s main insights are 1. There is a difference between a real and artificial constraint. And 2. The only real constraint of government spending is inflation and everything else is artificial. It is obvious that inflation is the most important variable to track and forecast in the MMT framework, so one must surprised to learn that MMT does not have a coherent model to forecast inflation. For example, The Deficit Myth never actually explores the most important question under Kelton’s MMT framework: if every prescription she writes actually gets filled, how would that affect inflation? Also, what do we once we are at the “real constraint?” Do we destroy those clinics in the name of true austerity? Do we shut down the newly built schools? Do we stop digging a tunnel midway? What about the Good Job Guarantee? What would happen if such vast increase in the of number federal jobs triggers inflation? Would the guarantee just go away? How do we tell those that had the guaranteed federal jobs? That their guarantee wasn’t really a guarantee? Would they have unemployment benefits, or would that be inflationary too? The complexity risk is extreme, and MMT does not offer any answers, Kelton simply states that these policies would be monitored by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to assess its impact on inflation. The CBO currently assess policies by projecting their effects on the deficit, which is arguably an easier task than projecting inflation.

Kelton also suggests that these policies better the society and therefore its real productive capacity, which should tame any inflationary pressure coming from the federal deficit spending. Therefore she recommends during a New York Times interview that government spending should thought of as “self-financing,” as the government “can pay its bills by sending new money into the economy.” 7 Yet the only way government spending is “self financing” in real terms is if these government projects generated more value than the initial investment, otherwise the self-financing idea is tautologically false. This is a very high bar for the government sector without a profit motive. Nevertheless, we are not talking about how inflation happens under MMT; we are doing a scenario analysis on the complexities of the consequences if inflation occurs under an MMT regime. MMT has no solution aside from denying the assumption that inflation can occur, because it cannot model inflation. If we cannot model inflation correctly then we cannot correctly forecast the inflationary impact of policy prescriptions. Without an ability to accurately forecast the most important variable in the MMT framework, any prescription based off the MMT framework truly is just politics masquerading as economics, and is infinitely complex and risky.

MMT & Reflexivity

Reflexivity is rooted in the philosophical idea of self-reference. Self-reference describes an entity’s feedback loop from and onto the entity itself. Self-referential statements may seem inconsequentially harmless or even whimsical, but is actually seriously explored in philosophy, computer science, linguistics, and many others important fields. The classical example, as Soros used, is “This sentence is false.” (Think about this sentence. If true, then it’s false. If it’s false, then it is true. Ad infinitum.) Reflexivity is a broader version of such self-referring feedback loops. Reflexivity occurs in events where entity A exerts an effect onto entity B, which leads to entity B to exert an effect back onto entity A, and the cycle repeats. Thus, as mentioned previously, the cause and effect becomes circular so the independent and dependent variable amalgamate together and become indistinguishable. Soro’s big idea was that financial market is mired in reflexivity, and that this reflexivity and fallibility create a self-referencing loop unto themselves and makes all decision making inherently uncertain, he calls this The Human Uncertainty Principle.

The reflexivity problem of inflation isn’t new. Economists and financiers have long separated inflation and inflation-expectation and understood that there is at minimum some self-fulfilling loop between the two variables. In other words, we have long understood that if we expect that general price level will increase tomorrow, we will push forward some future purchases to today, which triggers the inflation that we expected. We however do not know what the exact relationship is. Economists have dedicated their lives trying to explain inflation to minimal success. Stephanie Kelton herself says on the Macrovoices Podcast that inflation “is a dynamic process,” “a complex phenomenon” and that “there isn’t economist on Earth who can write down for you a model of inflation that will apply in all times across, space and time, nobody can do it.” This uncertainty with regards to measurement of inflation is the fallibility that gives reflexivity its starting point.

MMT’s reflexivity loop is as follows. Given that

- MMT prescribes to enable government to deficit spend up to the point of inflation (the real constraint)

- Expectation of enacting prescription under MMT may affect some people’s expectation of inflation because not everyone is a believer of MMT.

- Those changes in expectation of inflation will affect actual inflation.

- This puts us closer to the real constraint of inflation on point #1.

As we can see, beyond the inability to model inflation, just the presence of a large enough group of people who expect inflation to occur when governmental deficit spending is increased, will cause actual inflation. Thus even if we give MMT economists perfect ability to model inflation under MMT, the fact that there are nonbelievers of MMT still makes MMT fallible, and reflexivity can cause a self-referencing loop between inflation and inflation expectation. Again, MMT cannot model the single more important variable in its own model, and even if it could, due to reflexivity it still couldn’t.

The second flaw of MMT with regards to reflexivity resides in the fact that MMT creates a false dichotomy of a nominal ability and the real ability to pay back debt, when in reality the relationship of the two is reflexive. To understand this fundamental error, we need to ask why do we ever bother paying back any debt.

The late David Graeber wrote in Debt: The First 5000 Years that violence is the backstop to debt, and that is what enforces payment.8. Graeber goes as far as saying, “Any system that reduces the world to numbers can only be held in place by weapons, whether these are swords and clubs, or nowadays ‘smart bombs’ from unmanned drones.” What he is saying is that he who has the gun makes the rules. Graeber identifies correctly that a government is much like the Mafia and its monopoly on violence gives it the ability to settle any debt nominally. I thought this was a rather dark view of human enterprise, but I do think Graeber has a point here. Ultimately, what MMT is suggesting is that governments, and more specifically, The Federal Government of The United States of America, holds both the power to enforce debt repayment from almost any counterparty, including other soverign states, and can pardon any obligations it owes by fulfilling the obligation in meaningless ledger entries.

However, that view is ultimately assuming that debt is a single-shot game. In the real world, debt is a iterative game. I would argue that the practical reason to pay back your debt is to allow you the creditworthiness to take on more debt in the future. We have already explored above that creditworthiness is no different for governments. When MMT says that a fiat currency issuer will always be able to payback any debt denominated in its currency and thus never be insolvent, it is only the partial truth. What should be included is that this limitless repayment is only in nominal terms. A fiat currency issuing government can create limitless nominal financial assets – cash or bonds to offset any nominal debt obligations. However it does not mean that a fiat currency issuer can settle any real debts indefinitely. MMT has the incorrect idea that governments can offset real obligation with nominal repayments unless there is inflation, when reality is that if government offsets real obligation with nominal payments, it creates inflation. The reason is inflation is created when the storage of value function of the money deteriorates, and that demand for real goods exceeds demand for money. When settling real obligations with nominal payments, future demand for such nominal financial assets will drop because the creditors are not getting the real return they expected, and so their required nominal return is pushed higher in order to be compensated appropriately. This increased future required interest rate makes obtaining future funding more difficult for the debtor. The reflexive loop here is that using nominal payments to offset real obligations will increase the future nominal costs to offset future real obligations. This is inflation: ever increasing monetary costs to exchange for the same real goods/services. In essence, private businesses without a money printer go insolvent in nominal terms when demand for their financial assets drops too much, while governments with a money printer experience inflation when demand for their financial assets drops, and they go insolvent in real terms.

Fundamental Error of MMT: Human Uncertainty and Risk

We are at the last point of this overly long post on MMT. We’ve so far explored 5 mistakes of MMT. First, taxpayers do fund government spending. Second, Kelton’s prescription has innumerable unintended consequences. Third and fourth, MMT does not have a model of inflation that it desperately requires, and due to inflation expectation’s reflexive loop with inflation, it never can model inflation endogenously. Lastly, MMT’s prescription to offset real obligations with nominal payments will cause the inflation that disallows them to prescribe further. What this translates to is

- We don’t know if the MMT model is descriptively correct

- We don’t know the unintended side effects of MMT’s prescriptions.

- We don’t know how to measure the risks of those prescriptions.

- We do know that there are reflexive loops that amplify those risks.

My final point is fairly simple. As Soros said, fallibility and reflexivity makes all human affairs inherently uncertain. In an uncertain world, risk mitigation is far more paramount than being correct. When the government misunderstands deficits to be intrinsically harmful, and let’s be clear, it is a misunderstanding because deficits per se are not harmful; what is actually happening is that deficits are being using a imperfect heuristic to gauge the real danger: inflation and disintegration of the monetary and social system.

An old tale has it that due to poor ventilation technology, early coalminers were extremely vulnerable to dangerous concentrations of noxious gas buildup in the mines. So these early coalminers carried canaries into coalmines with them. The reason is that canaries are far more sensitive to these noxious gas buildups than the coalminers were. When the concentration reached levels sufficient to harm the canaries, the coalmines were evacuated. These little bird were the heuristic to an invisible risk, much like using a easily measurable figure in deficits as an early warning to inflation. MMT’s proposition is that we get rid of the canary in the coalmine, and butt ourselves right up to the uncertain limits of the inflation. Just like the dreaded carbon gases in those old coalmines, this inflation limit is invisible to our currently available tools, and just like the gases were deadly to the coalminers, the risk of inflation is existential to our society. Kelton’s suggestion that every government policy is to be assessed on its probability of triggering inflation is dangerous because she herself realizes inflation is currently almost impossible to model. Yes, the deficit is not an accurate gauge of inflationary pressure, and no, the current system is imperfect, and has caused much undesirable collateral damages. But putting a veneer of deficit hawking has served its purpose well enough as a heuristic, that until a demonstrably more accurate model of inflation can be constructed, it just seems unwise to scrap the canaries for a theory that has yet to resolve all of the problems mentioned above.

Reference

- https://www.businessinsider.com/alexandria-ocasio-cortez-ommt-modern-monetary-theory-how-pay-for-policies-2019-1

- https://www.theverge.com/2019/2/12/18220756/bill-gates-tax-rate-70-percent-marginal-modern-monetary-theory

- Kelton, Stephanie. The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy. Illustrated, PublicAffairs, 2020.

- Schwager, Jack. Market Wizards, Updated: Interviews with Top Traders. 1st ed., Wiley, 2012.

- https://www.georgesoros.com/2014/01/13/fallibility-reflexivity-and-the-human-uncertainty-principle-2/

- http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=9281

- https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/05/opinion/deficit-tax-cuts-trump.html

- Graeber, David. Debt : The First 5,000 Years. Brooklyn, New York`, Melville House, 2014.